Adoption History: Single Mothers-To-Be Incarcerated in Maternity Homes

Wayward Past

By Susan Gervasi, Washington City Paper, March 19, 1999

Before single motherhood and Roe v. Wade, unwed women rode out their pregnancies at a Northwest D.C. mansion.

Before single motherhood and Roe v. Wade, unwed women rode out their pregnancies at a Northwest D.C. mansion.

On Easter weekend of 1963, Pollie Wisham Robinson’s parents found out she was pregnant. The slender redhead was 16 and had been dating her 24-year-old boyfriend for two years. Her mother called her a whore and forced her to douche with Lysol. Her brother Joe, a military man stationed in suburban D.C., drove home to South Carolina to warn her that since their parents wouldn’t consent to a shotgun wedding, the baby would be called a bastard.

“I couldn’t go to church Easter Sunday,” recalls Robinson, now a South Carolina beautician. “I was soiled goods.” Instead, she was exiled some 400 miles away, to a gothic mansion on the edge of Georgetown called the Florence Crittenton Home. On the drive north in his blue 1961 Buick, Joe had explained that Crittenton would secretly shelter her until her baby was born and relinquished for adoption. She knew it was also a hiding place that would spare her livid parents the embarrassment of a ruined daughter.

Back in Spartanburg, her parents were telling friends that Pollie was baby-sitting Joe’s little boys for his hospitalized wife. The deception contained a grain of truth. Before entering Crittenton at the appointed time–the pregnancy’s seventh month–she spent weeks with the family in their Woodbridge trailer park. But the sense of shame she’d held at bay flooded back the day she walked into the mansion. “There were some girls coming down this stairway in the front hall,” says Robinson. “They couldn’t or wouldn’t make eye contact. They were looking downward, as if they were in a zombielike state. It gave me a feeling of sadness.” Her daughter was born two months later. “I named her Jacqueline Hope,” says Robinson. “Jacqueline for First Lady Jackie Kennedy, and Hope in the hopes I’d see her again.” But after her return to Spartanburg, it would be 20 years before she again laid eyes on Jacqueline Hope.

It was the ending Robinson’s family wanted. In sending Pollie to Crittenton, they had banished their daughter to a secret world where the disgraceful were hidden and disgrace disappeared. Between 1925 and 1982, thousands of women–many young, many scared, all pregnant–were sent to spend the final three months of their pregnancies at the home. At Crittenton’s height, some 400 women a year passed through 4759 Reservoir Road. Like Robinson, most left with nothing but memories.

Years later, it’s hard to understand the depth of the stigma that drove women into places like Crittenton. “My mother mainly did the hysteria trip,” recalls Florida nurse Emmy Sanford, in 1967 a pregnant Woodbridge 16-year-old. “‘What will the neighbors, family, friends think?’”

Karen Wilson was 17 when she left the Northern Virginia suburbs to live in a Thomas Circle brownstone while awaiting her seven-month-mark entry into Crittenton. Like many young women slated to enter the home, she took daily classes at the home while working for a D.C. family. At night she slept in a small attic room and studied the menacing spires of a nearby Victorian church.

“I really had no sense of where I was except that I was in D.C.,” Buterbaugh says. “I never left that house except to be driven to class at Crittenton and back every day, and I had no idea where that was. At night I served drinks at their parties. I was their ‘little unwed mother,’ a conversation piece.” Life inside Crittenton was no less surreal. Robinson recalls that each morning at 6 O’Clock, residents lined up to get two pills from a nurse–to this day, she doesn’t know what they were. They also received regular checkups by George Washington University Hospital residents.

High-school-level clients took classes in a cramped attic. Sanford recalls a labyrinthian journey through endless doors, hallways, and stairs to get there. “I felt like I was being snuck away to the attic where old and discarded objects were placed,” she says. “Once I was told to read The Bridge Over the River Kwai. I never did. To this day I have never been able to see that movie or hear that name without being taken back to the attic and with it all the sorrow.”

But avoiding sorrow had nothing to do with why people were sent to Crittenton. The $1,000 fee purchased a setup that shepherded babies to adoption while concealing their mothers’ identities–even from fellow residents. “We were instructed not to ask any personal questions, so no one could identify who we were,” says Buterbaugh, now a D.C. legal secretary. At the home, she was known–like all clients–only by her first name and last initial: Karen W. “When you’d talk to other girls, it would be like, ‘When’s your due date? Do you want a boy or a girl? What’s on TV?’”

But whether it was a boy or a girl usually didn’t matter. Unwed pregnancy violated “deeply rooted social and religious mores,” wrote a social worker in 1957 in one of hundreds of similar papers that guided the values of places like Crittenton. The cure, according to corrupted Freudian theory, involved surrender of one’s child to closed adoption. “One hundred percent of girls entered Crittenton intending to relinquish, and 86 percent did,” says Mary Green, a retired Crittenton social worker who was one of about a dozen folks who counseled clients in what mothers called the “gargoyle part” of the complex. “You didn’t want to go to the gargoyle part,” says a former resident, who dreaded trips from to her social worker. “It was only considered counseling if you talked about the adoption. We were given a piece of paper. On one side you were supposed to write down what you could do for your baby. On the other side you wrote down what they, the adoptive parents, could do for your baby.” “We said, ‘You have to look at both sides of the issue,’” says Green. “What it’s like to keep and what it is to release….Some girls literally would not talk about it. Sometimes the girls who weren’t ready to talk would come in with their knitting, and we’d just sit there and knit.” “I remember talking to this social worker once or twice, and I remember me telling her, ‘I can give my daughter love,’ ” says Robinson, who searched for and reunited with her daughter in 1983. “And she said, ‘These are the better parents for your child.’”

The Crittenton Home may have been all about secrecy, but at least part of its mission was very public. When the first tidal wave of baby boomers reached puberty in the early ’60s, thousands of them crowded the nation’s nearly 200 homes for the unmarried and pregnant–47 of which bore the Crittenton name. By the mid-’60s, Florence Crittenton Association shelters were housing some 10,000 clients a year–about one in every 30 unmarried and pregnant American females.

Crittenton Homes were the McDonald’s of maternity homes. There was one in almost every major city, thanks to the rescue mission launched by grieving gilded age millionaire Charles Crittenton and named for a daughter lost to scarlet fever. The fortress on Reservoir Road joined the network in 1925. In the days before Roe vs. Wade, the home was a cause celebre for philanthropic Washington. Gifts bestowed from the higher reaches of society were key to Crittenton life. Hundreds of volunteers lavished both money and time on the home. “It was like you were a charity case,” says 1966 resident Judi Batchelor. “It was somebody with more money and more prestige pretending somebody else was less fortunate.”

Cadres of knitters, for instance, churned out blankets and clothes for the newborns. “They would parade us out to raise money, while they knitted these little outfits for our babies–as if we couldn’t afford clothes for them,” says one mother. “But our parents were paying for us to stay there, and $1,000 was a hell of a lot for a two-month stay in those days. But they got contributions by saying, ‘these poor girls can’t afford clothes for their babies.’”

Social functions provided a chunk of Crittenton’s income, as well–along with public money, endowments, investment income, and United Givers Fund contributions. In 1968, the events included a “champagne fashion show at the Embassy of Belgium,” a “luau at the Shoreham Hotel” and Crittenton’s annual “Fountain of Flowers Ball.” The dances, dinners, and projects netted the home $60,000 that year. For social climbers, being asked to join one of Crittenton’s limited-membership circles was a coup. “We used to laugh about it,” says Green. “The Florence Crittenton board and circles thought they were equal to the Junior League. I got the feeling the people in the circles were aspiring to be on the board.”

Of course, the genteel outside world that kept Crittenton afloat sometimes collided with the socially unacceptable world within. Green recalls the day a board member–”a very elegant lady who lived in Cleveland Park”–was shocked to encounter the pregnant daughter of a neighbor at the home. “She was mortified,” recalls Green. “She said, ‘Why didn’t they send that girl somewhere else?’”

By the time Crittenton closed in 1982, after almost a decade of legal abortion–and at a time when increasing numbers of single mothers were choosing to keep their children–few mourned its demise. The home was sold to the Lab School of Washington, while the home’s organization was reborn as Florence Crittenton Services of Greater Washington–a Silver Spring agency that’s officially concerned with teenage-pregnancy prevention and with helping youthful mothers.

But the changes that put Crittenton out of business bothered some of its elderly volunteers, says Betsy Houston, a consultant who was on the board of directors when the home folded. “They were disillusioned that the girls didn’t seem to think it was a shame to be coming there,” says Houston.

Behind the arts and crafts classes, the knitting, and the card games lurked the inevitable and terrifying unknown of birth. Crittenton in the ’60s provided no prenatal education, though it did emphasize diet and health. The end of the pregnancies was the mansion’s final mystery. By the ’60s the 14-bed hospital adjoining the home was used only for mothers and babies after their return from George Washington University Hospital, no longer for actual deliveries. But a 1958 client has vivid memories of a bizarre chore she performed there while it was still a real maternity hospital. “There was a kitchen sink with a garbage disposal,” she says. “When the girls gave birth, we had to grind up the afterbirth in there.”

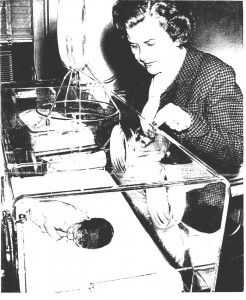

New mothers occupied a large curtain-divided ward. Babies were tended by nurses in a glass-walled nursery across the hall. Batchelor remembers secretly unwrapping her son’s blanket to peek at his arms and legs for the first time. “We sat in a little circle holding our babies, trying to feed them. Somebody would fall apart at every feeding, start crying. We would have to ask the nurses, Joanie and Barbara, to take the children back to the nursery….I was trying not to bond with him, which was stupid because I already had.”

Emmy Sanford watched her parents as they got their first glimpse of her baby through the nursery window. “The woman held Aaron up for them to see,” remembers Sanford, who like most mothers gave her baby a name knowing it probably wouldn’t stick. “I saw my father smile and laugh. He said, ‘Oh, look at those big feet!’ My mother swiftly gave him a light slap on his forearm as if to say, ‘You are not to enjoy this.’”

Catholic mothers often had their babies baptized at a nearby church, while Protestants could partake of an optional blessing given by a Lutheran chaplain in a dark-panelled makeshift chapel. They were “a very healing kind of thing, something that gave myself and the girl a lot of satisfaction,” says the Rev. Donald Piper of Silver Spring, now retired, who regularly visited the home in the decades before it closed. Robinson has kept the white Bible given to her by Piper for the ceremony, though she somehow lost photographs taken that day of herself, a friend, and their babies by the friend’s mother. “The only way she would take the picture was for us to switch babies,” says Robinson. “For me to hold Chris’s baby, and her to hold mine. So we wouldn’t have pictures of the evidence.”

Like Robinson, some mothers signed legal papers and left while their babies stayed behind. Buterbaugh rocked her daughter for an hour, alone in a room, until a nurse came to retrieve the infant. Others placed their babies directly into the arms of adoption workers. “I tried to give her a teddy bear,” recalls one mother. “I was told, ‘No, dear, you can’t do that. It has your scent on it, and we want her to bond with her new parents, don’t we, dear?’ We had to give the babies out by the loading dock, by the garbage cans. Was that to send us a message? That we were garbage? I gave her to the lady and started to cry. Then I ran upstairs to the attic and watched that car disappearing until I couldn’t see it anymore.”

“As a minor, she is legally under her parent’s control . . Thus, although biologically about to become a mother, she is socially a dependent child, prevented from making decisions that are ordinarily considered part of parental rights and responsibilities.” – HELPING UNMARRIED MOTHERS, by Rose Bernstein, copyright 1971